Artist Feature - Adam Wilson

Published on 03.12.2021 by Rachel

Published on 03.12.2021 by Rachel

Back in spring 2020, Adam Wilson contacted us to see if we could offer some support with the cost of materials on his final BA project for the City and Guilds of London Art School. The project he set himself was to create a replica of a gilded, ornate tabernacle frame from the Vento region made in 1520. We are so happy to share some of Adam's processes and knowledge on this project.

"The tabernacle frame is a variant of the cassetta frame common in Italy in the 15th century and are constructed around a robust backing frame with applied classical architectural elements. Typically they have an entablature comprising of a cornice, a frieze, and an architrave and in some cases applied imposts at each corner. The entablature is supported by pilasters with classical order capitals and stand on applied pedestals. These stand on a predella constructed in a similar fashion to the entablature with a cornice, frieze, applied pedestals, and carved mouldings.

The whole construction can be richly decorated by carving and applied ornamentation, gilded, polycoloured, and burnished to create an object which has jewel-like qualities and resembles a temple or tabernacle. Their original purpose was to house devotional paintings but were later used for secular works as well."

It is the gilding where the products from Handover are involved, but it would be a shame to not mention all the research, carving, sculpting, and molding that came before the gold! Adam meticulously carved and constructed the wooden frame that would become the base for the embellishments.

The embellishments themselves were sculpted from clay before making a mold and casting them in plaster.

Thin strips of clay were rolled out and applied to create the stem of the vine. These were laid on and would be trimmed, pressed on, and modelled later. Leaf forms were roughly sketched out by applying dabs of clay with a small Italian leaf tool.

"The original ornamentation is cast gesso grosso, without any animal glue, and has been coated with gesso sotille before being water gilded and part coloured with azurite. To remain faithful to the original I have made a batch of gesso sotille using the recipe from Cheninni’s Il Libro dell'Arte which involves slaking plaster of Paris in water for a good 30 days to convert calcium sulphate hemihydrate into calcium sulphate dihydrate, which was the original gypsum material used in Italy during the 15th. century for different types of gesso.

Gesso grosso is plaster of Paris and is sometimes mixed with animal glue to make modelled ornamentations for frames, but analysis by the V&A conservation department didn’t find any traces of protein in the cast gesso ornamentation, which indicates that the cast gesso is possibly plaster with a thin layer of gesso sotille on top to allow for water gilding and burnishing."

Once cast and attached to the wooden frame, the entire surface is prepared for gilding.

"After 1 hours mortar work the bole clay is ground to a fine dust. It comes in all sorts of natural colours and I'm using yellow for the base coat which supports the gold leaf. The bole gives the leaf a cushion against the hard gesso and enables a high burnish to be achieved on the work."

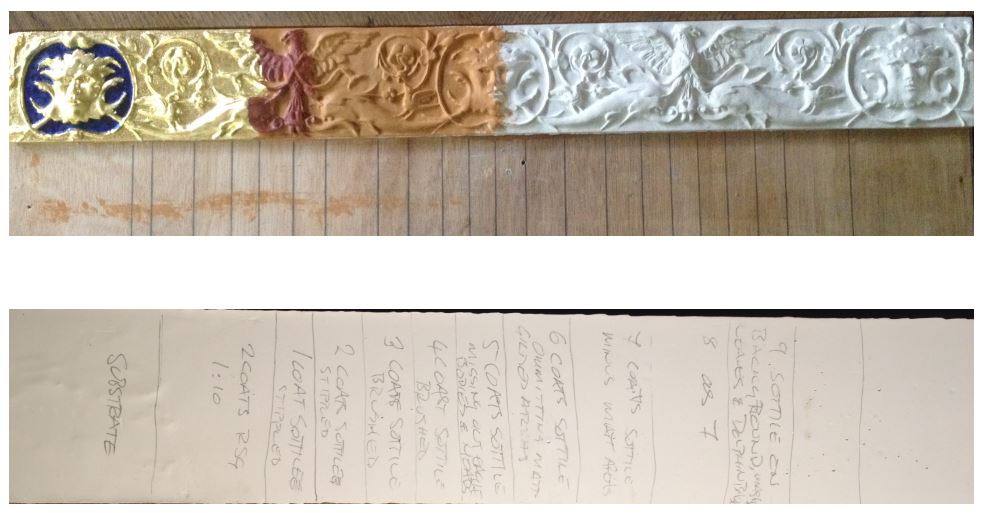

"I have made a test panel and applied it to a ply backing on which I can note each step of the gilding for reference. 9 coats of gesso were applied to an unfinished cast, along with 5 coats of yellow bole and three coats of red and the bole was burnished with a stiff bristle burnishing brush prior to gilding. I found that after applying so many coats of bole, I could leave the final burnishing of the gilding for as long as I liked and it was interesting to see the bole deflect under the agate burnisher. The cartouches were finally painted with ultramarine tempera, but I hope to use azurite on the final frame."

"The whole frame was covered with a single layer of Manetti 24 Karat leaf and the sight edge had three layers of 23 Karat Handover leaf. This meant that I had enough Manetti leaf left over to be generous with the faulting to achieve the coverage I wanted"

"As intended, the frame was not distressed after gilding to prevent damaging the delicate punch work on the plaster frieze and defeating one of the main objectives of the project.

I wanted to see how the frame change under different lighting which meant keeping the highly burnished finish. I believe that during the renaissance frames were left burnished as lighting levels in domestic and sacred settings were much lower than we have today and that the finish played an important part in the role the frame had to play.

As these frames were used as precious liturgical objects containing sacred images, they were made to be as glorious as possible and represented the boundary between secular and sacred spaces."

This is a quick overview of the years of work and research that Adam has put into this project. You can see more of Adam's work over on his Instagram here!

Hooray!

Product added to basket!